“In the business world, the rearview mirror is always clearer than the windshield” – Warren Buffett

The US stock market is at record highs, European markets are around five-year highs and the Japanese stock market is up almost 60% in six months. Times have been good for equity investors and yet the economic news continues to be far less bullish.

This is my attempt at peering through a dirty windscreen.

A current popular theory to explain this contradiction is that equity strength is all due to central banks — that their zero interest rate policy is artificially forcing investors into stocks. Another fashionable view is that there is a “disconnect” between GDP and equity markets which will be resolved through a sharp fall in share prices. Wherever you sit in this debate it is important to realise that the relationship between stock market performance and GDP is more complex than we often assume.

Nobel-laureate economist Paul Samuelson’s famous quote is particularly apt, that the “stock market has predicted nine out of the last four recessions”. I also rather like legendary investor Peter Lynch’s “if you spend 13 minutes a year trying to predict the economy, you have wasted 10 minutes” (which does suggest it may be worth spending three minutes a year on economic forecasting). The two comments together are damming of the many paid to predict and analyse both stock market movements, economies and the relationship between the two. Both the stock market and economic outlook are highly unpredictable, which is a good place to start.

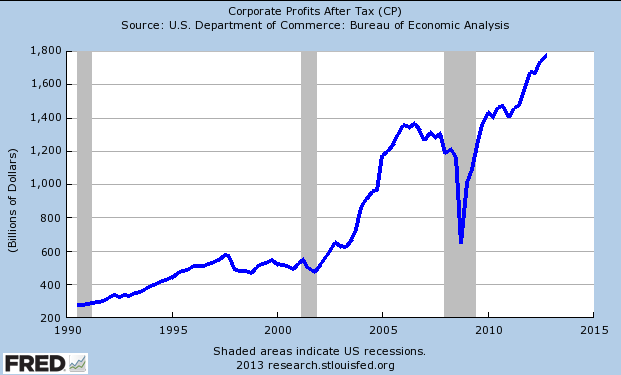

In theory, the economy should drive stock prices – strong output means higher corporate profits, therefore higher equity prices (and lower profits and prices for recessions). It intuitively makes sense. But already this is a gross over simplification. Corporate profits are strongly driven by executive decisions too, not just the economy. At the moment profit margins for American companies are at record levels because management is choosing not to invest and hire. This boosts profits and therefore share prices, even though the economy is weak (In fact it’s the lack of confidence that is stopping the companies spending). Many companies are also taking advantage of record low interest rates to increase their debt and return cash to shareholders either via dividends or through share buybacks. This reduces cost of capital and increases equity prices further. So the US economy may not be in great shape, but Corporate America is.

And in Europe, it is a similar story. Companies are performing a lot better than their economies. Partly for the same reasons as in the US – executives are keeping exceedingly tight cost control, thus margins are high – and European firms are also financing themselves on cheap debt. (In Europe though revenue is softer reflecting the weaker general outlook). Companies can be profitable in weak economies – as they are now. And of course there are many defensive companies who do well in recessions.

You don’t need to go that far back in the past to remind ourselves that strong economies can be catastrophic for equities. Remember the dot com boom? All that confidence and growth ensured executives believed in their own hubris. The TMT bubble that burst wiped out extraordinary amounts of corporate equity. In fact the final years before the collapse of the credit boom – the early 2000’s saw a dire performance from stock markets which peaked in 1999/2000.

There are other reasons why stock prices may not mirror GDP. About 70% of FTSE100 profits come from overseas so it’s more driven by global GDP than the what happens in the UK. Corporate Germany is also a massive exporter to the rest of the world.

Thus the discontent between stock markets – strong – and the economy – weakish – which so many find bewildering is explainable. Of course, a deep dark and sudden recession will wipe out corporate profits, but that is not the situation we are in. We’re in a slump that has been on-going for years – companies have had time to adjust and cut and rebuild from the initial shock.

At the same time central bank actions are forcing investors into equities. Getting 2-4% dividend yield with the potential for capital appreciation looks a good trade given the amazingly low yields on both government and corporate bonds. And PE valuations at low double digits are not expensive although not as cheap as before. But this is viewed as a low quality reason for equity market strength, not “real” as it were. But are any of the “reasons” we make up for why a market is rallying more valid than others? I wonder why we attribute a quality argument to this?

However there is one more explanation to stock market strength – that it is predicting a recovery in output that is already underway in the US and potentially the UK and that maybe even Europe is not that bad? A TUI Travel executive on Friday said that the “outlook for summer (bookings) is extremely strong particularly in the UK and Nordics”. That is extraordinary. Conventional wisdom is that the UK consumer is exceedingly hard up after the longest and largest fall in disposable income since the Great Depression. Yet Britons are desperate to book their week or two of summer on the beach (I do realise that British weather is dire and a strong stimulant to seek the sun).

The longer we go through the slump, the nearer the recovery is. Companies are sitting on huge amounts of cash and will get bored soon of not spending it. That cash will be earning very little either – reducing corporate returns. At some stage CFOs will decide it is better to spend the cash in building the business and as every day passes, that day gets nearer.

Maybe the simple relationship is still valid, that GDP and stock markets are linked. What we are getting wrong is markets are telling us that a recovery is underway….