Where have all the children gone?

In the long-term, the answer to every question is demographics. Changing ages and populations determine an enormous portion of which companies and countries will be successful.

At the same time, they're one of those things that moves so slowly that we rarely stop to consider them.

So the new buzzword/thing that people who talk about demographics are talking about is the 'second demographic transition', which immediately begs the question: What was the first demographic transition?

It is the shift from high birth rates to low birth rates as mortality rates fall. It's consistent globally and is marked by the shift away from very large families. It came with a lag in places where mortality rates fall, usually due to improvements in medicine.

The first demographic transition was initially thought to be the only demographic transition. The belief was that birth rates would level off around replacement at 2.1 per woman.

That hasn't happened. Instead, in most of the richest countries -- particularly the more-secular ones -- rates have fallen below that and in some cases, far below. The United States and UK are at 1.8, Canada is at 1.6. Italy is at 1.4, Denmark at 1.7, Germany at 1.4, Japan at 1.4, South Korea at 1.2 and China at 1.6 as of 2016.

The inclination is to believe that lesser-developed countries are still growing rapidly but that's not the case. Brazil is at 1.9 and all of Latam at 2.1, the Middle East and North Africa at 2.8 with the only truly high birth rate in sub-Saharan Africa at 4.8, which is about where the US was in the 1950s.

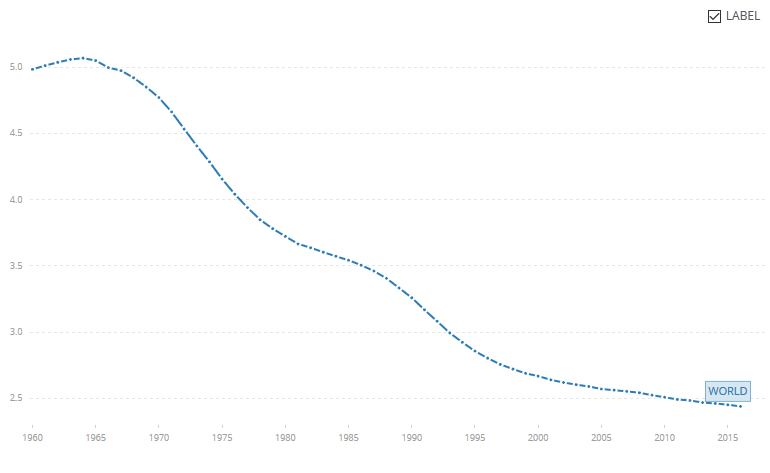

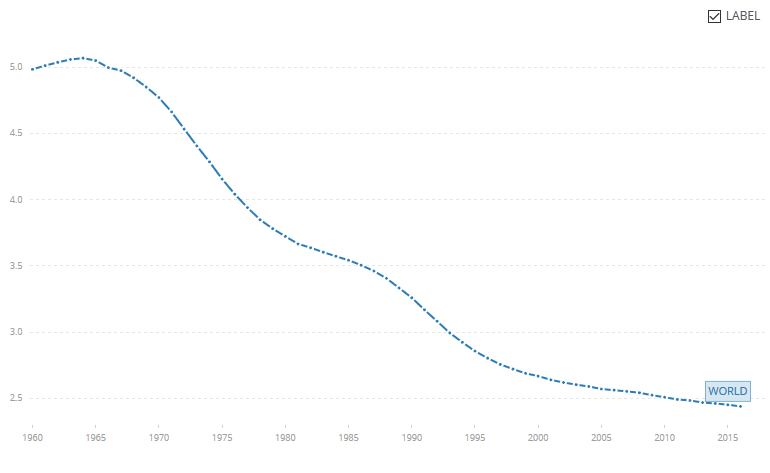

The world is at 2.4 and falling. The average woman is having half as many children as their mother. This is the second demographic transition.

You might be tempted to think this is a good thing because since Malthus more than 200 years ago, humanity has been fretting about overpopulation. Like all things in markets: When everyone piles into one side of the trade, it's the other one that wins out.

Why is it a problem for markets? I would conservatively estimate that half of corporate profits over the past 50 years have been due to a growing population and the rise of the middle class in emerging markets. All companies ultimately make things for people and if there are fewer people, there will be fewer profits.

Debt is a bit more complicated. In theory, the remaining people should be richer per capita than their parents and the excess savings will allow them to be creditors, which would make for a strong market for increasingly indebted countries, especially in an environment of falling stock prices due to lower profits.

However, higher per capital wealth isn't a given. Take housing. Even in an environment with a small surplus of housing, prices quickly fall. A house with no one to live in it isn't even worthless -- it's a ongoing cost due to property taxes. So if you bring housing values down to construction costs, that is a massive drag on per capita wealth.

What most countries have been relying on is immigration. It's the easiest way to supplement a declining population but I expect the glory days of immigration to the developed world are behind us. Rising wealth and living standards are helping to keep people at home, net migration in India and Brazil in 2017 was flat.

That likely means a future where countries compete for more aggressively immigrants or they lower standards, which could backfire into more pressure to close borders. Even the staunchest pro-immigration policymaker will admit that a doctor from India is more likely to make a positive contribution than someone who can't read.

Another option, and this is already underway, are government incentives to have children. France might be the best example of this. It has a strong social safety net and recognized the problems of a declining birth rate early on and is Europe's most-fertile country. Benefits include long maternity leaves, cash allowances and subsidized daycare and spending in the EU ranges from 2-4% of GDP. These policies have helped but even countries with the most-generous programs aren't particularly close to 2.1. France in 2018 fell to 1.88 in 2017 in a steady slide from 2.0 in 2014.

Even more frightening is the cultural change in views about having children -- the way we think about the purpose and meaning of children.

Historically, they were critical to replenishing the tribe. They were labour, a way to honour God, and perpetuate the family name -- a necessity. Now they're a lifestyle choice increasingly seen as a sacrifice and a commitment that's growth from 13 years to 18 years to 25 years and beyond.

As for what the future holds , your guess is as good as mine.