Is America stuck in a low-growth trap?

Interest in Larry Summers’ speech given on November 8 at the IMF’s most recent economic forum has been increasing. It did not receive much coverage at the time but is gradually being recognized for its importance. Essentially he raised the question as to whether “secular stagnation” was the new normal for America (and possibly Europe). He pointed out that Japan’s real GDP today is about half of what was forecast at the start of the Clinton administration in 1993. Summers then warns that the same may be coming to America – decades of subdued or zero growth.

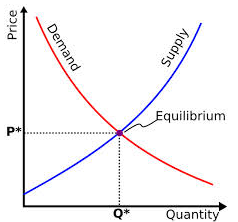

Essentially his argument boils down to the level of equilibrium interest rates. So a little theory first in order to understand the argument that Larry is making.

We all know what the classic economics supply and demand curve looks like:

As price rises, demand falls but supply increases . There is a price where demand for a product equals supply of that good which is where the price will normally settle in a competitive market. But this graph can also be applied to the supply and demand for capital, with the “price” of capital being the interest rate. What Summers is suggesting is that this equilibrium real interest rate, where savings and investment bring about full employment, is actually negative. Only at a negative interest rate would surplus savings (supply) be transformed into investments (demand). Thus interest rates, even at these incredibly low levels currently are still too high and so output / GDP is sluggish.

Summers’ argument

Summers looks back at the boom years before the crash and points out that pretty much everyone agrees that there was huge amounts of irresponsible lending and that households experienced wealth above and beyond reality. But he then states that this, highly unusually, did not have the effects such a boom normally would. So unemployment fell but not to extraordinarily low levels, inflation was well under control and capacity utilisation may have been high but was not extraordinarily elevated. So the usual economic data that normally signal an overheating economy were not doing so. To quote Summers, “even a great bubble was not enough to produce an excess of aggregate demand”.

He adds that the recovery in the US after this great financial crisis has been sluggish:

“The share of men, women or adults who are working today is the same as it was four years ago. (And yet) four years ago the financial panic had been arrested, the TARP money paid back, credit spreads had substantially normalised and there was no panic in the air. That was a great achievement. But in those four years since the share of adults that are working has not increased at all. GDP has fallen further behind potential…. And the American experience is not unique”.

Summers explanation for these two facts – little sign of US overheating before the crisis and sluggish recovery after – is that the equilibrium interest rate to balance excess supply of capital and demand for capital to invest, has turned negative. In Summers own words:

“Suppose that the short term real interest rate that was consistent with full employment had fallen to negative two or three percent sometime in the middle of the last decade. What would happen? Even with artificial stimulation to demand coming from all this financial imprudence you wouldn’t see any excess demand and even with a relative resumption of normal credit conditions, you’d have a lot of difficulty getting back to full employment”.

The practical problem with a negative equilibrium interest rate is that the Federal Reserve and any other central bank has great difficulty creating negative rates. And even if they could, the economy may still fall into a liquidity trap making such negative monetary policy ineffective. Just to remind you a liquidity trap is where consumers hoard savings rather than investing or spending them. So cutting rates doesn’t stimulate demand as consumers hoard liquidity (cash) as they fear for the future (deflation, unemployment etc). Thus Summers argues that even current low interest rates are not sufficient to stimulate the economy enough to produce full employment and output (GDP) will therefore remain subdued. More worryingly, the combination of what he sees as a negative equilibrium interest rate and the liquidity trap ensures that output may remain sluggish forever.

There are a few different interpretations of the Summers’ speech, Bloomberg’s –

Business Insider and Paul Krugman in the New York Times. Unsurprisingly Paul Krugman’s agrees with Summers:

“… you can argue that our economy has been trying to get into the liquidity trap for a number of years, and that it only avoided the trap for a while thanks to successive bubbles.” (Summers didn’t use the term liquidity trap but it is clear that is what he was talking about).

Clearly Summers is a great brain, after all he almost ended up as head of the Federal Reserve. But there are some flaws in his argument.

- Firstly, a liquidity trap means consumers hoard cash, which clearly shows up in a high savings ratio. But the savings ratio in America is anything but high.

- Secondly in the UK, unemployment did fall to a very low level in the boom time of under 5%.

- Thirdly and possibly most importantly the reason why the boom did not fuel inflation was that China joined the WTO in December 2001. This was extraordinary timing. In the last five years of the boom when inflation would normally have risen, it didn’t because the world was flooded with cheap Chinese goods. Thanks to its low cost labour force and undervalued currency China exported deflation to the rest of the world.

- Fourthly Chinese savings are immense because of the lack of any welfare system in the country. It may be that once the Chinese get a free national health service, a national pension scheme, or unemployment benefits, then that savings glut could be transformed into a Chinese consumer boom. When that happens the supposed negative equilibrium interest rate will turn decidedly positive. Chinese and Japanese excess savings are not a given forever.

Summers has raised some interesting thoughts and is provoking debate, all of which is good. But I think he is over intellectualising the problem. Reinhart and Rogoff show that a global financial crisis takes years to get over – much longer than a normal recession – in fact normally about four years. But they haven’t proved that after that the recovery is necessarily sluggish. The problem with the US recovery is the damaging effect that automatic budget cuts are having. Fiscal policy from Washington is the problem. It may be a less intellectually demanding reason that “negative equilibrium interest rates” but that does not mean it isn’t a reason.

I argued at the Kilkenomics festival two weekends ago that any “average” long term growth rate for a country is frankly ridiculous. Technological advances and all sorts of changes affect potential GDP. We know that annualised GDP varies from decade to decade. In the 70’s the high oil price induced inflation did much output damage. Post the Second World War, the American economy boomed. The industrial revolution, the creation of telecommunications, or the railways, all have had significant impact on GDP for the following decades. (If you are interested in these long term changes, the BBC is running a fascinating series at the moment on radio called a History of Britain in Numbers where Andrew Dilnot, Chair of the UK Statistics Authority brings “life to the numbers that highlight the patterns and trends that have transformed Britain”.)

So America is highly likely to be facing a decade of GDP that differs from that in the past but I doubt it has to do with a “negative equilibrium interest rate”! I imagine it will be due to the way we use the internet or social media or telecommunications, or an advance that we know nothing about currently.

But far importantly Summers does remind us that these great intellectual debates about economic theory are not just an “intellectual game”. That “getting these questions right makes a profound difference on the lives of nations and their peoples”. And it is especially important now as the world’s most powerful central bankers are all following the Fed’s lead. The ECB and the Bank of England are both committed to keeping interest rates low for years. Are we creating asset price bubbles again, in the stock and property markets? And do we have to have asset bubbles to prop up our economies from otherwise sluggish growth as Summers argues?

If you want to watch the speech yourself and come to your own opinion here it is:

It’s been an intellectual workout watching and analysing this speech but I have also learned that legendary economist Stan Fisher’s graduate course at MIT was numbered 14 462. And that Summers doesn’t think much of economists from the Universities of Minnesota and Chicago (but I need an American to explain that one).

Larry Summers’ ending thoughts:

(his eloquence and obfuscation may suggest a future career in politics)

“So my lesson from this crisis…. that the world has under internalised is that it is not over until it is over and that is surely not right now and cannot be judged relative to the extent of financial panic. And that we may well need in the years ahead to think about how we manage an economy in which the zero nominal interest rate is a chronic and systemic inhibitor of economic activity holding our economies back below their potential.”